I first came across this paper after seeing a post on Pen’s excellent blog, Is life worth living?. The study explores a fresh approach using Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) to target voltage‐gated sodium channels (VGSCs) for the management of chronic pain—a condition that afflicts millions worldwide and has long been the nemesis of conventional drug development. By degrading key proteins like NaV1.7 and NaV1.8, PROTACs may offer a novel therapeutic avenue for tackling pain at its source.

Pain Therapy: A Landscape of Progress and Frustration

For over two decades, the quest for non‐opioid pain therapies has seen its share of breakthroughs and setbacks. VGSCs such as NaV1.7 and NaV1.8 have emerged as particularly attractive targets. These proteins are heavily implicated in pain signalling and are preferentially expressed in peripheral sensory neurons, with mutations in NaV1.7 capable of resulting in either congenital insensitivity to pain or, conversely, heightened pain syndromes.

Figure 1. Human NaV1.8 apo protein.

NaV1.8 inhibitors like VX-548 have demonstrated efficacy in acute pain management, validating NaV1.8 as a target. However, conventional inhibitors offer only a transient blockade of channel activity and often suffer from off‐target effects and suboptimal efficacy. This underlines the urgent need for alternative approaches, which is where PROTACs come into their own.

PROTACs: A Different Kind of Drug

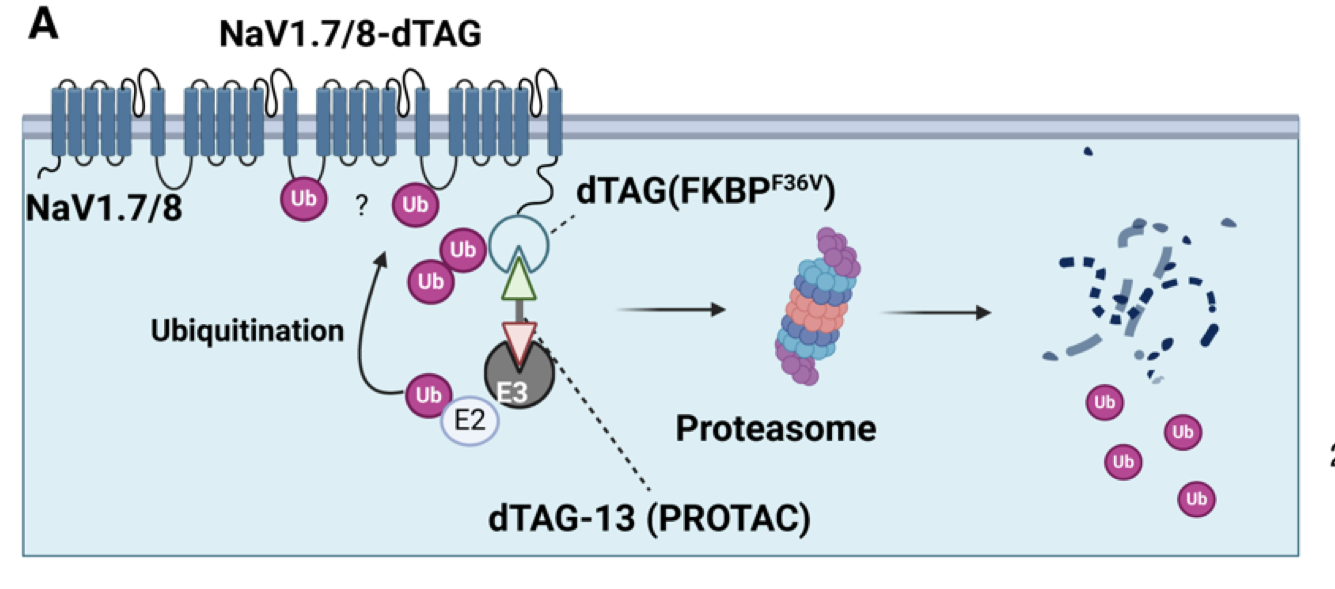

PROTACs represent an innovative leap in drug design. Rather than simply inhibiting a protein’s function, these molecules harness the cell’s ubiquitin–proteasome system to actively reduce the target protein’s abundance. By recruiting E3 ubiquitin ligases, PROTACs induce the degradation of proteins, thereby offering a sustained and more complete inhibition of pain signalling.

The advantages are multifold. Degrading a protein outright ensures a longer-lasting impact compared with mere receptor blockade—a potential game-changer for chronic pain. Moreover, while traditional drugs are confined to binding specific “druggable” pockets, PROTACs only require any accessible attachment point on the protein to trigger degradation. Acting catalytically, a single PROTAC molecule can tag multiple proteins for degradation, which may also translate to lower doses and reduced side effects.

This recent study demonstrated that NaV1.8 and NaV1.7 are in fact amenable to PROTAC-mediated degradation. Researchers engineered these channels with conditional degron tags—such as dTAG and SD40—to facilitate selective recognition by PROTAC molecules. For instance, the use of a C-terminal FKBP12^F36V tag in the dTAG system, coupled with CRBN-recruiting PROTAC dTAG-13 or VHL-recruiting dTAG-v1, led to robust, dose- and time-dependent degradation of NaV1.8.

Figure 2. Schematic showing NaV1.7 and NaV1.8 with FKBP12F36V (dTAG) appended to the intracellular C-terminus.

Figure 2. Schematic showing NaV1.7 and NaV1.8 with FKBP12F36V (dTAG) appended to the intracellular C-terminus.

This degradation was confirmed to be proteasome-mediated through inhibition studies with bortezomib, while mass spectrometry pinpointed ubiquitination at lysine 1100 on the second intracellular loop of NaV1.8. Similar degradation patterns were observed for NaV1.7, particularly with C-terminal tagging yielding higher efficiency than N-terminal modifications.

Interestingly, candidate PROTACs based on non-specific sodium channel blockers failed to degrade unmodified NaV1.8, underscoring the necessity for novel intracellular binders. Notably, surface-expressed NaV1.8 was completely eliminated, demonstrating the functional relevance of this approach and opening up entirely new ways of thinking about pain therapy.

Why this Matters for Pain

Ion channels are notoriously challenging targets. Their dynamic nature and complex conformational landscapes, coupled with their often inaccessible locations in peripheral neurons, mean that traditional small molecule inhibitors have repeatedly fallen short. By eliminating the target ion channels altogether, PROTACs bypass many of the limitations inherent to conventional inhibitors. Moreover, if this strategy works for NaV1.7 and NaV1.8, it raises the tantalising possibility that other pain-related channels—such as TRPV1 or PIEZO2—could also be targeted.

Challenges Ahead

However, several hurdles remain. The current experiments have utilised engineered, tagged versions of the sodium channels. While the in vitro data is promising, the paper leaves open the question of whether wild-type, unmodified channels can be similarly targeted in vivo. Comprehensive animal studies to assess pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution, and long-term safety will be crucial to validate the approach and move beyond these initial experimental limitations.

The broader challenges inherent to PROTAC drug discovery compound the issue. Crafting molecules that can effectively bind to the complex intracellular sites of ion channels is no trivial matter, especially given that many pain-related targets reside in peripheral neurons that are notoriously difficult for systemic drugs to reach. Innovative delivery strategies are essential, as is the need to ensure high selectivity; even slight structural similarities among VGSC subtypes risk off-target degradation of channels such as NaV1.4 or NaV1.5, which could lead to severe side effects. Furthermore, the large, hetero-bifunctional design of PROTACs often results in poor membrane permeability, short half-lives, and rapid clearance, all of which complicate their overall pharmacokinetic profile.

Beyond these PROTAC-specific issues, challenges unique to pain therapy further complicate the landscape. Chronic pain is driven by a multitude of mechanisms, including central sensitisation and inflammatory signalling, meaning that targeting a single ion channel subtype may not suffice for comprehensive relief. Inhibiting one VGSC subtype may even trigger compensatory mechanisms —such as the upregulation of other subtypes—that diminish the intended therapeutic effect. These complexities underscore the necessity for multifaceted approaches when addressing the intricacies of chronic pain.

Despite these challenges, the potential of PROTACs in the realm of pain therapy is enormous. They could fundamentally reshape our approach to targeting pain, providing a much-needed reset button for a field that has long been mired in obstacles. While they are not a panacea, PROTACs offer a new way of addressing pain at its very source, and possibly even extend their reach to other neurological conditions.

For a field that has been stuck in a cycle of partial solutions, this innovative approach is certainly worth watching. Let’s see where it takes us next.